In Richmond Hill’s “Little Guyana,” Election Season Brings Focus to ‘Crabs in a Barrel’ Tensions

Richmond Hill, NY – As election season ramps up in Richmond Hill, organizers along Liberty Avenue say they are confronting a challenge that rarely appears in campaign mailers but regularly surfaces in private conversations: internal rivalries that can fracture turnout, volunteer networks, and fundraising in a neighborhood trying to translate cultural visibility into political power.

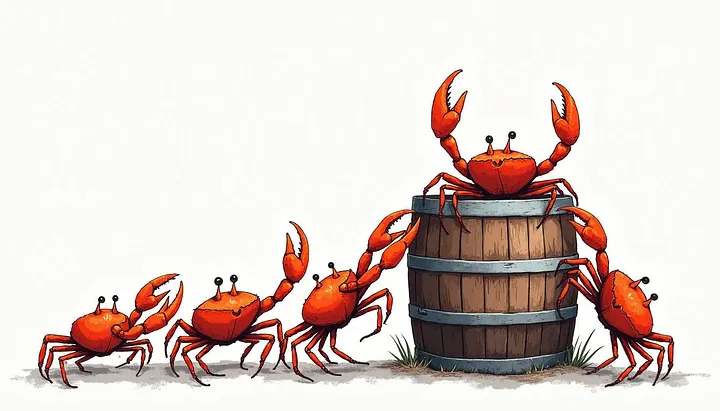

The dynamic is often described with an old metaphor, “crabs in a barrel,” shorthand for the idea that when one person begins to climb, others pull them back down. The phrase can be used casually, but local advocates say it captures a real tension they see during elections, when competition for influence intensifies and trust across families, religious institutions, and community organizations can become fragile.

With federal and local political stakes rising and voter outreach expanding in “Little Guyana,” the question is no longer whether the community is large and organized enough to matter. It is whether it can sustain unity long enough to matter at the ballot box.

A neighborhood learning its electoral weight

Richmond Hill’s Guyanese presence is prominent enough that the city co-named a key corner “Little Guyana Avenue” in 2021, a symbolic recognition of a diaspora that has shaped commerce and culture in South Queens. (QNS)

In recent cycles, civic groups have also increased election-season activity in the area. Caribbean Equality Project has hosted voter engagement events branded around “Little Guyana Votes,” including a 2024 outreach program at the same Richmond Hill intersection known for its shops and restaurants. (Caribbean Equality Project) In 2021, a similar “Little Guyana Votes” rally and canvass effort was reported as aiming to strengthen political participation in a largely immigrant community, with organizers emphasizing the need for voters to “build political power.” (QNS)

The neighborhood sits within Queens Community District 9, where NYC’s voter participation data shows a registration rate below Queens overall and citywide levels (78.7% versus 84.5% for Queens and 85.2% for the city), and where general election turnout in 2022 was noted as lower than the city average.

Elections are also a recurring forum for questions of representation. A 2019 community town hall in Richmond Hill highlighted what organizers described as a gap between South Queens’ growing South Asian presence and the lack of South Asian elected representation in city and state office. (Queens Daily Eagle)

Where the “crabs” metaphor comes from, and what it means now

The metaphor is usually explained as an image: if one crab is alone it can climb out, but when crabs are together, a crab trying to escape is pulled back down. In human terms, it is used to describe sabotage, rumor campaigns, gatekeeping, and social punishment aimed at anyone seen as getting “too big.”

Historically, the phrase has circulated in multiple communities, often as a warning about inward conflict. In a 1923 essay written for Current History, Marcus Garvey described internal divisions and wrote that Booker T. Washington had used a “crabs in a barrel” comparison in lectures. That reference is notable because it is secondhand: it documents Garvey’s claim about Washington’s use of the story, not a direct Washington text. (UCLA International Institute)

For Richmond Hill organizers, the relevance is practical, not literary. They describe campaign seasons where personal feuds or organization-versus-organization competition can override shared goals like voter registration, candidate forums, or coalition building.

What research suggests is happening under the surface

Psychologists and organizational researchers use different terms, but many point to a similar set of mechanisms:

Social comparison is one of them. In his 1954 paper, Leon Festinger argued that people evaluate their abilities and standing by comparing themselves with similar peers, a process that can become emotionally charged when a close “peer” suddenly moves ahead. (SAGE Journals)

Workplace researchers have also examined a related pattern directly. A study in Frontiers in Psychology on “crab barrel syndrome” found associations between social comparison processes and pull-down behavior, with competitive “Type A” traits linked to higher likelihood of the syndrome and lower self-esteem linked to stronger effects. (Frontiers)

A third factor is scarcity. A widely cited study in Science found that poverty and scarcity can impose a cognitive load that narrows attention and reduces mental bandwidth, making it harder to plan and making short-term threats feel urgent. Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir have argued in this research tradition that scarcity can “tunnel” focus toward immediate problems at the expense of longer-term goals. (Science)

Applied to elections, that combination can look like this: when the stakes feel limited and reputations feel fragile, some community actors may interpret another person’s rise as a threat to status, access, or donor attention, rather than a shared gain.

A local history of survival, and the costs of internal division

Community advocates in Richmond Hill often situate these tensions in a longer story of migration and survival.

Many Indo-Guyanese families trace ancestry to the indenture system that brought Indian laborers to British colonies after the end of slavery. The The National Archives notes the breadth of records tied to Indian indentured labor and the historical terminology used in colonial documentation. (National Archives)

For organizers, the point is not to flatten Indo-Guyanese life into hardship. It is to explain why “scarcity thinking” can be culturally sticky: when earlier generations learned to survive in systems with restricted mobility, the instincts that protected households can sometimes resurface as inward competition in a diaspora setting where opportunities still feel scarce, especially in housing, small business, and political access.

Effects in election season: turnout, trust, and credibility

In Richmond Hill, the harms described by organizers and local civic groups are often less dramatic than open conflict but more damaging over time.

One is fragmentation: multiple groups may run parallel voter registration drives, forums, or endorsements that do not coordinate, reducing collective impact and confusing voters. Another is reputational warfare: candidates and organizers can become targets of rumor, personal attacks, or purity tests that discourage future leadership.

The downstream impact, organizers say, is a weaker negotiating position with elected officials. The community may be large, but if it is publicly divided, candidates can pursue votes without committing to specific policy priorities, or assume that the neighborhood’s influence is not cohesive enough to swing a race.

At the same time, community institutions argue that Richmond Hill is not defined by sabotage. Indo-Caribbean Alliance, Inc. describes its mission as unifying Indo-Caribbean and South Asian interests and connecting residents to government and services, positioning itself as a “welcome center” in Richmond Hill. (INDO-CARIBBEAN ALLIANCE, INC.) Supporters of this view say mutual aid, entrepreneurship, and dense family networks have allowed new arrivals to stabilize quickly, even when politics becomes noisy.

What remains unresolved

As elections approach, the “crabs in a barrel” metaphor is increasingly used as both diagnosis and warning: a reminder that internal division can become a political liability, especially in a neighborhood working to convert demographic strength into representation and policy wins.

Whether Richmond Hill’s election-season energy turns into sustained political power may depend on what organizers call the hardest task of all: building enough trust that competition does not cancel out collective progress.

Sources used

- NYC Votes Queens Community District 9 Community Profile

- “Little Guyana Avenue” co-naming coverage (QNS)

- “Little Guyana Votes” voter outreach coverage and event pages (QNS)

- Garvey (1923) excerpt hosted by UCLA on “The Negro’s Greatest Enemy” (UCLA International Institute)

- Festinger (1954) “A Theory of Social Comparison Processes” (SAGE Journals)

- Uzum (2022) “Crab barrel syndrome” in Frontiers in Psychology (Frontiers)

- Mani et al. (2013) “Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function” in Science and Princeton summary (Science)

- The National Archives research guide on Indian indentured labour (National Archives)

- Richmond Hill representation and civic participation reporting (Queens Daily Eagle)